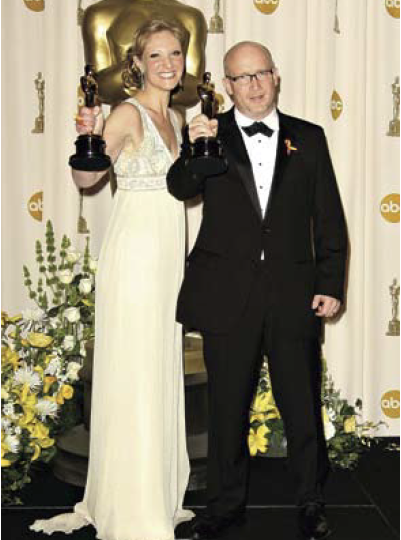

Academy Award winners: Taxi to the Dark Side producer Eva Orner and director Alex Gibney

February 2005 and Eva Orner was doing it tough. She’d endured a long New York winter marked by blizzards and heavy snows, new in town, out of work, low on friends and short on cash. But one of her few buddies, someone she’d met back home in Melbourne, invited her to an Oscars party at his apartment in Tribeca. There, with Ground Zero out the window and A-list glamour on the TV, a dozen thirtysomethings sat on the floor with Indian takeaway on their laps and watched Jamie Foxx, Morgan Freeman, Hilary Swank and Cate Blanchett scoop the pool. “We all had to put in $50 for an Oscars sweep,” says Orner. “I was like, ‘My God, 50 bucks!’ ” But she won, and walked out with $600 to put towards the rent of her studio apartment eight blocks away. “I was so happy,” she says. “It was really handy.”

Fast-forward to February 2008. Eva Orner is standing on the stage of the Kodak Theatre in Los Angeles, wearing $100,000 worth of Bulgari diamonds, accepting her Oscar for best documentary feature from Tom Hanks, focusing on a smiling George Clooney to stay steady in her high heels. “It was kind of crazy,” she says. “At that party in New York, I was a new kid on the scene. I was asking them all for contacts. It was a scary time. Three years later, I was at the Oscars, you know, in the good seats.”

Orner, 38, won her Oscar for producing Taxi to the Dark Side, directed by veteran American documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney. Their 100-minute film is an unflinching unpicking of the story of Dilawar, an Afghani innocent who was tortured and murdered by US soldiers at Bagram Air Base. Dilawar’s tale is the springboard for a wide-ranging examination of prisoner treatment in the war on terror. It’s harrowing and politically acute and very dark. When I meet Eva Orner in Melbourne, she is bright and chatty and very cheerful. She greets me at her mother’s large, lived-in house in bayside Brighton, tells me she’s starving, and leads me to her hired hatchback so we can go and find some food. “I hope I remember to drive on the left,” she says. I buckle up. We make it to St Kilda, Orner in motormouth mode all the way, enthusing about Melbourne, stressing her sleepiness and, nevertheless, how much she’s looking forward to catching up with old friends. She parks a metre from the kerb but only 20 metres from Cicciolina restaurant where she orders fishcakes and a rocket and parmesan salad. She’s been away 3½ years: I suppose she can be forgiven for saying “parmesahn”. “I haven’t been back at all for 18 months,” she says. “That’s just not cool. But at least I have an excuse. People know I’ve been busy. It’s not like I’ve been swanning around.”

Well, she did swan around on Oscars night. First, she got frocked up. “When we got nominated, I called Collette Dinnigan’s office in Sydney and said, ‘Hi, I’m Eva, the other Australian [i.e., not Cate Blanchett] who got nominated.’ ” A gown was soon on its way. Then there were the diamonds. “That was hilarious. Suddenly I had a guy dropping all these diamonds off at my hotel. I’d never worn a diamond in my life, but you put on a $30,000 earring and all of a sudden you get it. They light up your face.” Then there was the limo (“My hotel was half a block from the theatre but it took 45 minutes for it to crawl along”) and the red carpet – “People want to talk to you but they’re more looking behind you.” Inside, Orner “got kind of tense. I had a train and high heels on and I’m incredibly klutzy. My biggest fear was falling on my face.”

Then Tom Hanks came out to present the documentary award. “He said, ‘And the Oscar goes to …’ and I heard ‘T’ and we were up. It was just crazy.” She was glad that she’d pumped Oscar winning Crash producer Cathy Schulman for advice a few days before. “She said to take a small mirror – this is so girly – because it’s a pain to go to the toilets to check your lippy. She said, ‘If you win, it’s so overwhelming, just focus on one person.’ That’s why I stared at George Clooney. I think he got a restraining order out,” she laughs. Tom Hanks was “sweet and funny. We walked off stage and as we got out of earshot, he said, ‘You can say ‘f…’ now. I let out this mighty ‘f…!’ ”

Then, champagne, media, parties, “a sea of happiness and pride and gratefulness”, marred only by dropping her phone down three flights of stairs, smashing it and checking back in at 5am, 700 messages later. “It keeps coming back to you that, my God, it’s an Oscar,” she says. “At the same time, we made this film about terrible things, so it’s not like you just forget them.” There’s footage in the film, shot on a mobile phone, of a woebegone prisoner smashing his head against the wall. “It’s the most disturbing thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” she says. “I’ve seen it a million times and it kills me every time.”

There’s no job description for film producers but, basically, they’re the people who get films made. They source the money and spend the money. They have input into script and casting, and an overseer’s role in shooting and editing. Good producers are unflappable, tireless and suffused with can-do. They soothe egos, solve disputes and know exactly when to produce a bottle of red. They can talk the talk till the cows come home, and start up again as soon as they’re in the barn. Above all, producers need to be intrepid networkers: if they’re well connected, they’re well ahead of the game.

Eva Orner could tick all these boxes, bar one, when she followed a love interest to the US in 2004. She knew the ropes from 10 years of work in the Australian film and television industry, but she was far from well connected in the US, especially after her relationship unravelled within weeks of her arrival. Nous and persistence, crucial qualities in a producer, got her through. “The first few months were tough,” she says. “I must have sent out 300 résumés.” She soon realised that some Australian cultural norms were a hindrance. “Back here, I’m this pushy bitch. I know I talk really fast,” she says, really fast. “But I still seemed to be very quiet in America. Here, you don’t want to stand out, you don’t want to be ‘me me me!’ In America, if you’re like that, you miss your opportunity.”

She became louder and more assertive under the tutelage of a Harvard-educated banker she started dating. “He was quick to tell me that I needed to stop with the shy thing. He was also aware of my very Australian intonation, ending a sentence to make it sound like a question. He told me it made me sound younger and more insecure.” He picked her up on it every time. “I’d say something and he’d say, ‘Statement or question?’ It became a running gag but I got it.” She also worked hard at getting connected. “Any time I got invited to something, I would never take a date because, if you go with someone, you just stand in the corner and chat. I would walk in terrified, a sea of people I didn’t know, and start introducing myself. I would choose someone who looked interesting and say, ‘Hi, I’m Eva. I’m a producer. I’m from Australia. Are you going to be my friend tonight?’ It was that tragic, but it worked.”

Being Australian was a great ice-breaker. “I never say ‘g’day’ and I’ve never eaten Vegemite in my life but they love Australians in America, and I am so trading on being Australian for the next 50 years.” The breakthrough came when one of her new contacts introduced her to Alex Gibney, director of the attention-grabbing documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, and on the hunt for a producer. “Eva had fiction and nonfiction experience and a wicked sense of humour,” he tells me via email. “What’s not to like?” The pair collaborated on a documentary about musician Herbie Hancock in 2005 and, in 2006, made The Human Behaviour Experiments, about psychological studies in the 1960s and ’70s of torture, bystander apathy and prisoner/guard dynamics. This film was the precursor to Taxi to the Dark Side, completed in 2007.

Orner brought skills and smarts to Taxi , but her cheerful presence was also important in keeping the gruelling production moving. “Part of being a producer is to drive the team,” she says. “Good managers are always smiling, they’re never having a bad day.” She rarely got ruffled. “The shit hits the fan all the time in filmmaking, and you just can’t fall apart. Everything is fixable.”

The team’s next film, Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr Hunter S. Thompson, overlapped with Taxi. It was a relief to work with lighter subject matter and to exercise different skills. “On Gonzo, Eva was charming and relentless with Jimmy Carter and [1972 presidential runner-up] George McGovern until they agreed to appear,” says Alex Gibney. “Who knew that the lady from Down Under would have such a way with American politicians?”

She credits her composure to meditation, two 20-minute sessions every day. “It gives me clarity,” she says. “I don’t freak out.” She learnt her mantra reciting technique at the Maharishi School in Melbourne eight years ago. “I was struggling, I took everything personally,” she says. “The first day I meditated, I walked out to buy my newspaper and I noticed a rosella. I had never seen a rosella in suburban Melbourne in my life. You just see things differently. You see more.”

Eva Orner grew up in Melbourne, first in middle-class Ormond, then more salubrious Brighton. Her parents, Henry (who died in 1998) and Diane, both survived the Holocaust to arrive in Melbourne in 1958. The Orner children – Eva and older brother Michael – breathed the past. There was always a box of clothes and tinned meats by the door, to be smuggled back to the Polish nanny who had hidden Diane during the war. “I remember seeing my dad stuffing money into socks and sending them over,” says Orner. How does she think the Holocaust impinged on her? “It must bear some weight that you hear those stories. I think I always had an ear out for injustice.”

The family made a more-than-comfortable living from Orner Engineering, a mechanical engineering company that made garden tools and car parts. Eva went to the Jewish high school Mount Scopus, which specialised in turning out future doctors and lawyers. She was a keen ballerina and skier and entered speech and writing contests, but there were slim creative pickings at school and she was one of only six students to enrol in Year 12 English literature. The teacher took them to see Brecht, exposed them to poetry, engaged them in salon-style conversation. “Mrs Dowse said she had to teach us all how to think,” says Orner. “She changed my life.”

Orner saw the classic Australian coming-of-age film The Year My Voice Broke during her final months at school. “That was when I thought I wanted to make movies.” She went to Monash University where she majored in visual arts, fell in with a filmy crowd and started writing film stories for The Melbourne Times local paper. “I thought if I wrote enough glowing stories someone would give me a job,” she laughs, only half joking. It didn’t work, so she started a production company, Fertile Films, with Sarah Barton (then Sarah Stevens), a friend from French class. Barton had been to film school and was a few years older. “I had a sense Eva would make a great producer,” she says. “She’s got a wonderful, upbeat energy. I felt she had her father’s business sense, but also a desire to do something that had meaning to her. It was a delightful combination.”

Henry Orner donated office space and the young women cold-called in search of corporate video work. They got a few jobs, including a 44-minute instructional film, How to Change the Engine of a Maytag Washing Machine. “We filmed it on a 40-degree day at a disgusting laundromat,” says Orner. “The mechanic was sweating and swearing and bleeding.”

In 1993, Orner and Barton spotted an advertisement calling for SBS documentaries. They pitched a film on disability and sexuality, directed by Barton and produced by Orner, prompted in part by Barton’s experience dealing with an exhusband with acquired brain injury. “The budget was handwritten because I didn’t know how to use Excel properly,” says Orner. “We really had no idea.” A month later, she ducked into the office to check the answering machine and discovered they’d been given $200,000 to make their film.

Despite their inexperience, Orner and Barton worked diligently. Barton found Orner, then just 24, “intelligent and creative but responsible and solid on the management side”. She also demonstrated good people skills. “A lot of people give their time for nothing on documentaries. You want to make them feel good, whether it’s providing a nice lunch, sending a thank-you, getting them along to the screening. Eva understood how to make people feel special.”

Untold Desires went on to win an AFI award in 1995 and a Logie in 1996 but, says Orner, “I couldn’t pretend I was a hot-shot producer.” She made a characteristically strategic move, talking her way into a job as production manager on the high-rating TV series Blue Heelers. “I didn’t know what vision switching was and suddenly I was in charge of 100 people,” she says. The show’s producer, Ric Pellizzeri, took a chance when he employed her. “We were looking for a people person,” he says. “We could teach her the nuts and bolts of being a production manager, but you can’t teach anyone how to be a warm, communicative human being.” He admired the way Orner made connections. “She’s a great networker,” he says. “You’ve got to play the game in this business, and she plays the game in an open, honest way.” Heelers was substitute film school. “I was there for two years, I did 200 hours of TV. I worked my arse off,” says Orner. “It was the smartest thing I ever did.”

She dipped a toe into feature films, co-producing Elise McCredie’s Strange Fits of Passion, and did some more TV. Orner had just finished the SBS documentary Secret Fear when her father died after a short illness. “It was devastating,” she says. “I deal with it by reminding myself that so many people have terrible parents. I had a fantastic dad and I’m so lucky that I had him for 28 years.”

She then moved to Sydney to work at the government-backed Film Finance Corporation as project manager. “It was all about the holes,” she says. “It matured my knowledge. I saw every deal, met all the players.”

After two years at the FFC, Orner ticked off film finance and, in 2003, worked with director Pip Mushin on his low-budget feature Josh Jarman. One of the film’s backers was Melbourne businessman David Harris, who became Orner’s mentor. Orner and Harris now speak at least once a week to assess opportunities that come her way. It’s not an obvious fit: one of Harris’s businesses collects coathangers from large retailers, ships them to China for cleaning and sorting, then returns them to Australian stores. “But I’ve got a long history in business and a bit of life experience,” says Harris. He thinks his protégé is hardworking and competent, likes the fact that she’s a dog-lover – “a very nice trait” – but puzzles over her unmarried status. “She’s probably looking for a man named Rover,” he says.

Orner is a sponge for advice on strategic moves. She’s honed her “Hi, I’m Eva from Australia” routine. “Now, when I go to Sundance or the Logies, I’ve got a list of people I want to meet and things I want to talk about with them,” she says. “I’m like a charming stalker.” At the Sundance Film Festival this January, for example, Orner tracked down her hit-list of five within the first two days. She’s now working on projects with two of them. Sydney producer Miriam Stein travelled with Orner to the Cannes Film Festival in 2002 and was impressed by her chutzpah. “Sting was standing in the corner; she went over to him and suddenly we were hanging out with Sting. There’s a fearlessness about her. That’s part of what makes a great producer.”

Eva Orner’s verve and gift of the gab are plain to see. She also has a nice line in multi-tasking, able to pick up mid-sentence after being interrupted by an email pinging in on her iPhone. She’s appealingly down-to-earth, worried about how much she should tip Australian taxidrivers (“I gave a guy five bucks and he was like, ‘What are you doing?’ ”) and succumbing to a minor flap about finding seamless undies for the Logies (they’re on the following night). She worries that her rave about meditating is “too hippie dippy” but swears she believes in karma and lays out her green credentials (she drives a Prius, she’s pescatarian) with unaffected sincerity. “I think you should try to live your life with the most good,” she says.

Encouraging other people to do the right thing will be a big part of future projects. “I’ve often felt frustrated,” she says. “It’s not like I’ve joined the Peace Corps, I’m not a doctor. What I do is entertainment and I don’t think that’s ever sat 100 per cent right with me.” She wants to work on “stuff that’s socially conscious, not just fluff”, and hopes to reach that person in middle America sitting on the couch eating Doritos. “If you show them something in an exciting, sexy way, maybe it will make them do something different.” Or maybe not. “It’s a big stretch. I don’t kid myself that a film will change the world, but if you can start a dialogue, it’s worthwhile.”

One thing she has to do is find a home for her Oscar: she’s just moved to LA and is house-sitting for now. But from the moment she was given her four-kilogram trophy, she realised he was a very unusual appendage. He had to be lugged from party to party on the awards night – “you can’t put him down because someone will swipe him” – and he caused hysteria among a paparazzi pack who didn’t even know who she was. “My dress was torn. It makes you more sympathetic to the celebrities.”

For the rest of the week after the Oscars, the statuette waited in the hotel. “Whenever I came in and saw it by my bed, I laughed.” When it was time to fly out, she inquired of Alex Gibney, “How do you get the little sucker out of here?” Hand luggage was the answer. “You have to swaddle it,” she says. Leaving Los Angeles was easy – “They see it all the time” – but flying into Brisbane was a different story. “I was at the X-ray machine and the guy yells out, ‘Who’s got an Oscar?’ It was uncomfortable. I got the hell out of there.”

When Orner has finished her fishcakes, salad and green tea, we head back to her mother’s house and she takes me to her pink-curtained teenage bedroom. There, on the desk next to a laptop, DVDs and neat piles of paper, is the gleaming award. It has that odd look of an object usually seen in a different context: your boss in bathers, for example. She offers to take a photo of me with her Oscar. “Nah, that’s okay,” I say. “Really? Everyone wants a photo,” she says. Apparently, people will also pay big bucks for the real thing. “I did a bit of Googling about how much I could sell it for,” she says. “I was teasing my brother, saying, ‘I reckon I could get a million bucks for it.’ He was saying, ‘No! Don’t!’ I told him I was kidding. I’m really proud of it and I’m really proud of the film. It sounds corny, but it’s such a gift.”

That may be, but it’s not Eva Orner’s style to sit back and soak up the glory. “This year isn’t about reflecting, it’s all about propelling,” she says, ever strategic. “My big word for the year is ‘maximise’.”

First published in The Age, Good Weekend, June 7, 2008

Eva Orner is also the director of the documentary, Chasing Asylum.

Leave A Comment