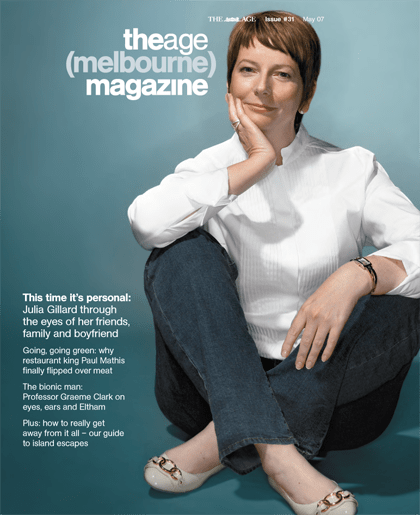

Our Julia.

If the opinion polls are right, Julia Gillard is on her way to becoming the most powerful woman in Australian

politics. It’s no surprise to those who know her well, writes Dani Valent.

Click the image above to read the article as it appeared in the age (melbourne) magazine

Julia Gillard is handed a water balloon and invited to take her best shot. She palms the quiveringly full blue

missile, assessing its weight. “I’m not sure about chucking it,” she says to the cheerful middle-aged woman

who proffered the ammunition. Who’s the target, anyway? Is it Joe Hockey, the Minister for Employment and

Workplace Relations, Gillard’s industrial relations opponent in Parliament? Is it long-time sparring partner

Tony Abbott?

Or is she going to sneak a shot at Kevin Rudd and wrest the Labor leadership after all?

No. Today’s victims are contestants in the Great Australian Dunny Race, part of the annual Weerama Festival

in Werribee, which is in Gillard’s seat of Lalor. Teams pushing homemade rickshaws mounted with toilets

thunder along Watton Street while the crowd piffs water balloons at them. Julia Gillard decides not to join in.

She gingerly lays down her weapon, making sure it doesn’t explode over her black trousers and

chunky-heeled boots. “I can’t afford to lose a vote,” she says, sipping a latte she picked up at McDonald’s on

her way to the festival. It’s not true – in 2004, she could have thrown away a few thousand votes and held

Lalor, a safe Labor seat. Still, an election year probably isn’t the time to be taking chances.

Gillard’s day continues as she clambers down from the knee-high VIP stage and mixes with constituents,

including a shy year 12 student who is presented by her mother (“It’s a hard year. You can’t study all the

time,” says Gillard brightly) and an unshaven old codger who wants to talk tariffs. “We need good industrial

policy, not tariffs. Not even Toyota asks for tariffs,” she says firmly, thinking perhaps of a recent meeting

with Toyota executives who were stunned that Gillard managed to ding her late-model car despite its parking

sensors. (“A bollard jumped out at me,” she explained.) Then, black tea and a strawberry with local mayor

Shane Bourke, a doorstop interview about industrial relations that turns up on the evening news, a Lutheran

school opening in Newport, a quick trip back home to Altona to grab supplies for a week in Parliament (“I

pack quickly”) and a 7pm flight to Canberra, where she bunks down in a Deakin hotel. So much for Sunday.

If you place any store in the opinion polls, Julia Gillard, 45, is going to be Deputy Prime Minister of

Australia before the year is out, the first woman ever to be so. Folksy distractions such as the Dunny Race

may have to go by the wayside. Gillard hopes not. “When I do things like that in the electorate, I can exhale

and be myself,” she says. “They like it that I’m in the media and I’m doing well. That gives the community a

sense of achievement. But because I’ve known them for so long, most of them think, well, that’s just Julia.”

Being “just Julia” is a big deal for Gillard, even if she is headed for one of the top jobs in the land. She’s hung

on to the ocker voice that has earned her a lot of snobbish stick (the accent, by the way, doesn’t stand out at

all in her home seat). She’s unapologetically childless, cheerfully unmarried (though she has a boyfriend) and

blithely admits she’s a terrible cook. “I can do toast and cheese on toast. I did make soup once last year.

It was edible,” she says, noting that she stood in the supermarket for 15 minutes wondering whether it would

be OK to substitute a swede for a turnip.

Her dyed red hair will still often look just one bad-hair-day away from unruly (even though the boyfriend is a

hairdresser). She’ll still be a member of Labor’s left faction, which has historically been locked out of leadership positions at federal level. She’ll still be clumsy, funny, unflappable and – as everyone who knows her says with robotic predictability – “down-to-earth”. It seems a fair assessment. The first time we meet, at

this magazine’s photo shoot in March, Gillard jokes about her small “inbred Welsh coal miner” feet as she

flaps around in too-big pumps supplied by the stylist. She tries on a cropped, padded jacket and checks

herself out sceptically in the mirror. “I could be an extra in Star Trek,” is the verdict. Later, she hops into the

front passenger seat of her chauffeured Commonwealth car then, when the driver traps her by parking hard up

against a lightpole, she scrambles across his seat, makes a joke about stealing the car, then tumbles out onto

Elizabeth Street. She ad-libs her way through an address to a small crowd of union workers gathered in

Bourke Street Mall for an International Women’s Day rally, then deems the gathering “cute” as she strides up

Bourke Street.

Gillard crosses the tram tracks halfway up the hill (“Ooh, look, Deputy Leader jaywalking”) and bursts into Il

Bacaro restaurant laughing. Her throaty giggle gets a good work-out over lunch where she seems delighted to

be upsold calamari (“Now, that’s Melbourne”), waves away the wine list (“On the wagon,” she stage-whispers

to the waiter) and wonders whether my microphone will pick up business talk from adjoining tables (“Sell

BHP!”). She’s good company. She listens. She’s that winning kind of smart person who doesn’t let the rest of

us feel dumb. (When a host on Channel Nine’s The Catch-Up asked Gillard’s media adviser whether John

Howard could still be Prime Minister if he lost his seat, Gillard considered it a “reminder” that we’re not all

politics buffs rather than an opportunity for dismayed mirth.) Of course, Gillard is selling herself, but the

pitch is seductive; if she was flogging TVs, you’d probably come home with a plasma.

So what is she actually offering? Julia Gillard flew high through student politics, industrial lawyering and

Labor Party backrooms, then battled her way through a jobs-for-the-boys ALP to stand for the safe seat of

Lalor in 1998. After nine years of wrangling, wangling, finagling and finessing, she’s vice-captain of the ALP

“dream team”, the personable foil to an upright, uptight Kevin Rudd. She’s the Opposition’s attack dog when

it comes to industrial relations, laying into Hockey and Howard whenever opportunity presents and

promising to roll back the Government’s WorkChoices laws should the ALP win government.

Her other portfolio, Social Inclusion, is a new one at the federal level. “It’s about cross-government

co-ordination to try to help people who get left behind in a time of economic prosperity,” she explains. It

sounds like an easy one to write off as amorphous “fair go” fluff but, if you believe Gillard, this stuff goes to

her core.

At the very least, it’s a way she can display her skill for connecting the political and the personal. You see it

when she’s talking to her “constits” in Werribee. You see it in a doorstop interview when she describes how a

cleaner loses money under an Australian Workplace Agreement. And you see it when she turns up to

Question Time with flyaway hair. She reckons people should be able to fulfil their potential, despite

inauspicious beginnings, despite the fact that they’re a woman. As both an example and a proponent of this

philosophy, Julia Gillard’s most important offering is herself.

You wouldn’t doubt her commitment, but Gillard isn’t 100 per cent focused on the main game. For the first

time in her life, she’s with a man who does not breathe politics. Tim Mathieson, a sales representative for PPS

Hairwear products, doesn’t fit the same mould as her other big loves (university sweetheart Michael

O’Connor and 1990s squeeze Bruce Wilson were both union officials; Craig Emerson, her boyfriend in 2002,

is a Queensland federal MP). “It’s just the way it’s worked out,” says Gillard. “In the heady days of student

politics it wouldn’t have occurred to you to have a relationship with someone outside of politics because it

was so intense and so much of your life.” Strangely, the closer she’s got to real power, the easier it has been to

love someone who isn’t involved in that world. “It’s the right thing at the right time,” she says. Part of what

makes Mathieson, 50, right is that he doesn’t care to talk about the finer points of IR over dinner. “I’m sort of

a lightweight in that area anyway,” he says. “She’s talking about that with high intellects all day, every day.

We just talk about life stuff or joke around. She can switch off.”

Mathieson has been the subject of snide whispers. What does she see in this hairdresser? Shepparton-born

Mathieson has been cutting hair on and off for 25 years, including at his own salons in Shepparton and on the

Gold Coast. He spent much of the 1990s in San Francisco where he and an old Shepp mate exported vintage

Levi’s and supplied marble interiors. In 2004, he was head stylist at Fitzroy’s Heading Out salon and it was

there he first chatted with Gillard when she came for appointments with another stylist. “There was a nice

connection there,” he says. They bumped into each other on a Collins Street tram just after the 2004 election

defeat and “there was a bit of a nice spark”, but Mathieson moved back to Shepparton to run a salon two

weeks later and Gillard had a busy few months considering whether to run for the Labor Party leadership.

They didn’t meet again for a year, when Mathieson moved back to Melbourne and gave her a call. Their first

mineral-water-only meeting was over lunch at Enoteca Vino Bar in Carlton North (“I got chastised by her

friends – ‘What! He didn’t buy you any wine? Get rid of him…’,” says Mathieson.) They saw Syriana at

Cinema Nova, in Carlton, the next week. By their third date, at Fitzroy’s Provincial Hotel, the spark had

turned into a bit of a flame. “It’s nice to meet a girl who’s grounded. I hate spin and there’s no pretence about

her in any way,” he says.

Mathieson is divorced and has one daughter, Sherri, 22, who works in Melbourne as a beautician. The two

women get on well. “Sherri has done Julia’s make-up for a photo shoot and I think we’re going to the opening

of the netball,” he says. Gillard doesn’t see herself as a step-mum. “No, I wouldn’t say that,” she says. “She’s

an independent adult. We see a little bit of her but she’s got better things to do with her life than hang out with

a couple of old people.” Having Sherri on the scene doesn’t seem to have awakened a desperate hunger for

children. “It’s human to ponder it but not with a sense of anxiety and regret,” says Gillard.

The couple don’t share a house. He lives in Northcote with “two crazy guys”, old schoolmates who work in

construction. “I’ve joked that living with me is a bit of an academic concept,” says Gillard, who is usually in

Melbourne just a couple of nights a week. “We’re used to it. It’s our version of normal.”

When she does come home, the sleepovers happen at her place. Mathieson will often have dinner ready.

“Fresh vegie soups and pastas, a whole lot of vegetables and beans. She eats out all week so it’s nice for her

to come back to something healthy,” he says. Home life is prosaic: sleeping in, strolls along Altona beach,

coffees out, and evenings in front of the telly (she likes The Bill, he likes motor racing). Gillard doesn’t find

switching gears hard. “It doesn’t take much for me to feel relaxed and away from it,” she says. “We dag out,

fairly significantly, pretty quickly.”

Friends say that Gillard is content. “He seems to have given her a bit of a stronger grounding,” says Julie

Ligeti, a mate from student politics days who is now chief of staff to Victorian Attorney-General Rob Hulls.

Robyn McLeod, who has been close to Gillard for 15 years, says, “They’re a very grounded, sensible couple,

dealing with an extraordinary time in her career.” She compares the situation to a couple of years ago: “Julia

wasn’t in a relationship and my marriage was ending and we’d sit around talking about blokes.

She said, ‘Men, they’re just net energy takers.’ And we’d talk about whether we had time for them or not.”

She’s glad Gillard has made time for Tim Mathieson. “I love seeing her so happy.”

Mathieson describes himself as “fairly bipartisan” but “definitely aligned with Labor Party values”. He

doesn’t plan on playing much of a role in the election campaign. “Her and Kevin, the dream team scenario,

they’ll be campaigning on that,” he says. But he has pitched in with his expert skills in hairdressing. After she

took on the deputy leadership last December, Mathieson thought “the focus needs to be on the topics, not on

everything else”, so “I thought we might just cut the hair and control it a bit more,” he says. The haircut took

an hour-and-a-half. “It was more daunting that she was my girlfriend than Deputy Opposition Leader,”

he says. “There was a slight bit of nervousness but I’d worked on it in my mind. Nothing was left to chance.”

Which is probably how Julia Gillard likes it.

In many ways, she is the arrow shot from her father’s bow, the bullseye fulfilment of his migrant dream. John

Gillard grew up in Cwmgwrach, an impoverished Welsh coalmining village, where his father worked as a

labourer. The eldest of seven children, John Gillard relied on milk and treacle dished out at school and he

remembers “chasing kids in the yard for a bite of their apple”. Even so, he developed a love of literature,

history and politics, which even then he saw as a way to bring change for families like his own. At 12 he was

reading the newspapers (“I could give you the wartime cabinet in England,” he threatens, speaking on

the phone from his retirement village in Adelaide) but at 14, despite being one of the top students in his area,

he was forced out to work. Jobs with a grocer, the Royal Air Force, the Coal Board and the police department

followed. While working as a policeman at Barry, where his duties included shining a torch on courting

couples at a local lovers’ lane, John Gillard met Moira MacKenzie, a local girl from a slightly more genteel

family, who worked at police headquarters as a clerical assistant. After they married, John Gillard left the

police force to become a booking clerk for British Railways. At night, he studied. “I’m a frustrated scholar,”

he says. “I would love to have gone into politics. I always felt I didn’t have the academic requirements or the

drive.” Bring on “social inclusion”.

When John and Moira Gillard had Alison in 1958 and Julia in 1961 they devoted themselves to ensuring the

children were able to fulfil their potential. Moira Gillard used Dick and Dora books to teach the girls to read

and write by the age of four. “Other women would tell her it was bad for the baby’s brain, you’ll do them

damage, but she kept on with it,” says a non-brain-damaged Julia Gillard. The initial catalyst for leaving

Wales was Julia’s health. She had recurring bronchial infections and a warmer climate was recommended.

But it was the chance to improve the family’s prospects, as much as the Australian sunshine, that saw the

Gillards take a £10 passage to Adelaide in 1966.

You get the sense that life was rather intense and quiet in their bungalow in aspirational Kingswood, a

southern suburb of Adelaide. John Gillard worked in a cheese factory before training as a psychiatric nurse.

He worked long shifts, often at night. Moira Gillard looked after a couple of local preschoolers then, when

Julia started school, took a part-time cooking job at a Salvation Army home for old women. “Our whole

thrust was to earn the money, pay the mortgage, get the kids through uni. We both worked like Trojans,” says

John Gillard. Julia Gillard doesn’t recall any arm-twisting, “But I had a sense that your parents have moved

halfway around the world to give you a better life. There was an expectation you’d go as far as you could. It

was in the ether,” she says.

Neither girl was terribly naughty (the worst anyone can remember is that Julia came home late from a school

dance). High jinks were restricted to pursuing Goldie the cat, who chased a series of escapee budgerigars.

There was some mild mean-big-sister stuff from Alison, who scared little Julia with the spectre of toxic trees

on a nearby street. “I used to try to push her into these ugly, knobbly trees and tell her she would catch an

awful disease,” recalls Alison. Both girls were good students and Julia, especially, didn’t need to be coaxed to

study. “Quite the opposite, we had to hold her back a bit. She was hitting the books,” says her father. Her first

taste of public speaking was as part of an Unley High School debating team that often trounced the local

private schools. The time her team was forced to argue “that the man should lead” was an exception. “I don’t

think we were very persuasive that night,” she allows. Gillard also played hockey “really badly” and was

elected prefect in a “muted form of democracy,” in which students could vote for students preselected by the

teachers. Would that all her elections were so easy.

Political discussion was part of the fabric in the Gillard household. “We’d be out in the kitchen getting the

lamb chops for the evening meal and the cry would go out, ‘Gough’s on! Gough’s on the TV!’ ” says John

Gillard. “We’d leave the chops and listen to the commanding, towering Gough.” Julia remembers her father

tuning into Question Time on the radio, “yelling back and forth as if he was a participant. Maybe that was the

start of it all,” she muses. Certainly, she can’t remember a time she wasn’t interested in current affairs.

She earned straight As in her matriculation, enrolled in law at the University of Adelaide in 1979, and snared

a spot as student representative on the University Council where she sat alongside “intimidating but kindly”

judges and dames and had her first experience of lobbying for change, in this case for student services. She

joined the Labor Club to campaign against education funding cutbacks (John Howard was Treasurer). Gillard

loved the energy of student politics but railed against “10-hour meetings in which nothing actually got done”.

She found her place in reining in the debates, bringing structure and order to “politics unplugged”. She also

realised she was a good speechmaker even though it made her “very scared”.

When she was elected education vice-president of the Australian Union of Students (AUS) in 1982 she

deferred her studies and moved to Melbourne, into a share house in Brunswick. Old friend Julie Ligeti was

struck even then by how serious Gillard was about politics. “We were all trying to work out how we were

going to buy our first car or which share house we were going to live in. Julia had this other level happening.

She was beginning her career in politics.” Personal ambition and agitation for change appeared to dovetail.

“She had a clear view at a very young age that she wanted to make a mark in Labor politics. But it wasn’t just

about identifying her own opportunities, she was also trying to push society along,” says Ligeti.

In 1983, Gillard was elected president of AUS for the year. She worked to make the organisation relevant,

shelving long-running debates on Palestine and the distribution of water from the Ganges River and turning

attention to student concession cards, housing, welfare and travel. “I learnt a lot about the need for whatever

you are doing to be connected to what people are worried about,” she says.

Her term up, Gillard completed law and arts degrees while working part-time for Socialist Forum, a left-wing

think-tank formed by disaffected Communist Party members in 1984. She became a member of the ALP’s

Carlton branch in 1985. In 1987, she joined Slater and Gordon as an industrial lawyer, then became the firm’s

youngest – and only its third female – partner in 1990, aged 29. While Gillard represented unions in their

battles with employers, the personal negligence arm of Slater and Gordon went after the top end of town

(BHP over Ok Tedi, CSR over asbestos and Dow Corning over breast implants) and pushed the firm into the

red to do so.

“They were very expensive cases. We often worried about whether we were going to make next month’s

payroll,” says senior partner Peter Gordon. Julia Gillard “made an important contribution” to managing the

accounts, and always supported the social justice cases. “She was always a proponent of doing the more

visionary things. It went to her core.” She was well-liked, at least until “tensions in the partnership” (as

Gillard describes them) set in.

“It was a robust environment, it was working-class male dominated, not a place for shrinking violets,” says

Peter Gordon. “She had a knack for injecting a spirit of goodwill and consensus into a debate. She had the

ability to defuse tension and acrimony, whether it was with the lawyers for the employers or around the Slater

and Gordon partnership table. It wasn’t a bad training ground for a politician,” says Gordon.

Gillard must have thought so, too. She had contested two Labor Party preselections but was stymied by a

sexist, undermining culture. “The tougher it got the more my determination grew to go into federal politics.

There’s a stubbornness there,” she says. She ran as number three on the 1996 Senate ticket, just missing out

on office after a six-week vote-count. After the 1996 Victorian election, she went to work as chief of staff to

John Brumby, then Victorian opposition leader. Around the same time, she worked with mentor and former

Victorian premier Joan Kirner and others to help form Emily’s List, a support network for ALP women. “We

were totally browned-off that women had to wait for the grace and favour of the blokes to get in,” says

Kirner. By the time the 1998 election rolled around, Gillard had managed to secure preselection for Barry

Jones’s old seat of Lalor. Joan Kirner, for one, wasn’t surprised that Gillard stuck at it. “Julia’s tough. She

understands there’s a lot of conflict in politics. She doesn’t focus on the person, she focuses on the issue,” she

says.

After the 2001 election, Julia Gillard took on the population and immigration portfolio and got plenty of

attention for her unstinting pursuit of Philip Ruddock over refugees. But she alienated many in the Labor

Party, especially those in her own Left faction, by crafting the compromise immigration policy that Labor

took to the 2004 election. Gillard’s proposal retained mandatory detention and temporary protection visas,

which many party members saw as a sell-out. Carmen Lawrence resigned from the front bench in response.

Detractors say it’s an example of the way Gillard will make soul-destroying compromises to play the political

advantage. Supporters praise her knack for crafting realistic policy. Speaking generally, Joan Kirner says

Gillard is a good negotiator. “She stands by what she says but she doesn’t insist on her outcome. She might

say, ‘Well, if that’s what we’ve got for now, let’s make this our way forward.’ ” She’s a big believer in shades

of grey. “The sort of policy decisions that face modern society – inter¿generational disadvantage, indigenous

health, the drug problem – they’re not the stuff of black-and-white solutions,” says Gillard. She enjoys

crafting policy solutions from muddied waters, finding a mid-point between pragmatic politics and “the

vision thing”. “I actually like those sorts of tasks. That’s what sort of politician I am,” she says.

In mid-2003, Gillard became Labor’s shadow minister for health. She became known as much for bantering

repartee with Health Minister Tony Abbott as for millstones such as Medicare Gold. “Most days Tony Abbott

is worth a laugh,” she says. “He’s an amusing and eccentric character.” Gillard was a loyal Simon Crean and

Mark Latham supporter and considered running for the leadership herself when Latham resigned in early

2005. Instead, she pulled behind Kim Beazley for one last hiding-to-nothing. Then, in December 2006,

Gillard checked her own ambitions to stand at Kevin Rudd’s shoulder. Surely now that Labor is looking like a

good bet in the next election, she wishes she was leader, not deputy. “No, I made the decision and once it

settled on me I’m comfortable with it,” she trots out crisply. Gillard doesn’t pretend to play squeaky-clean

politics, but you get the feeling she’d look you in the eye as she worked her cut and thrust. “I’m not naive

about the internal gaming but I haven’t made it the thing that I do,” she says.

Everyone in her family seems to recognise some sort of steel in Julia Gillard. “She always seemed to know

what she wanted,” says her mother. Still, no one predicted her trajectory. Alison Gillard finds it hard to

reconcile the strident, forthright politician she sees on television with her pliable little sister. “She was quite

sweet, fairly quiet. She never used to yell. I always wonder where that confidence and ability came from,” she

says. Her mother says they sometimes laugh about it. “There’s nobody else like that in our family, not that we

know of,” says Moira Gillard. “Sometimes I wonder where the heck she came from.” Her father is full of

pride. “I’m ecstatic,” he says. “Julia could have stopped in law and got on the gravy train but she’s doing what

she wanted to do. She’s compassionate, she feels for the poor, she has idealistic dreams.”

At the Weerama Festival, after the dripping Dunny Racers have wheeled their toilets away, it’s Julia Gillard’s

job to judge floats as they parade past the VIP podium. She claps and waves as the Girl Guides, a dog

obedience club, dance schools, brass bands and the Werribee Tigers football club shuffle along. The water

balloon lies forgotten at her feet. Well-wishers approach from time to time to congratulate her on recent

favourable polls. “You’re going to get them, Julia,” says one man. “Oh, well, you never know until you

know,” she says, thin-lipped, contained. Later, she says to me that she refuses to become excited. There’s too

much work to do. “You have a sense of tossing fortune to the wind,” she says. Fortune, yes, water balloon,

no. (m)

Leave A Comment