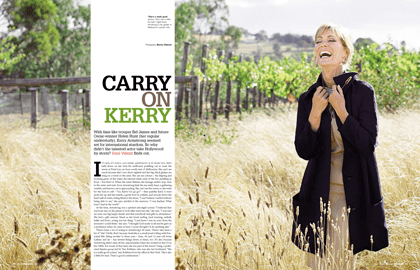

With fans like trouper Sid James and future Oscar-winner Helen Hunt (her regular understudy), Kerry Armstrong seemed set for international stardom. So why didn’t the talented actor take Hollywood by storm? Dani Valent finds out.

This article originally appeared in Good Weekend, 2008.

It’s 1975, it’s dawn, and Kerry Armstrong is 16 years old. She’s belly-down on her twin-fin surfboard, paddling

out to meet the waves at Point Leo, an hour south-east of Melbourne. She can’t see much because she’s very

short-sighted and her big, thick glasses are lying on a towel on the sand. She can see colours – the dipping and

looming green of the water, the blurred white soles of the boy paddling in front – but that’s it. When the water

flattens, the teenage surfers stop, turn in the water and wait. Soon Armstrong feels the sea swell, hears a

gathering rumble, and knows a set is approaching. She can’t see the waves, so she waits for the boys to yell –

“Go, Kerry! Go go go!” – then paddles hard. A wave picks her up and she stands, a goofy-foot in a bikini, and

swoops down the hard wall of water, riding blind to the shore. “I can’t believe I surfed without being able to

see,” she says, startled at the memory. “I was fearless. What trust I had in the world.”

At the time, Armstrong was a spirited schoolgirl actress. “I believed that everyone was on the planet to look

after everyone else,” she says. “I was sure we were one big happy family and that everybody had gifts in

abundance.” She had a gift, anyway. Much as she loved surfing (and running, netball, ballet and boys), acting

was her thing. “I just knew I was an actor from the moment I could think,” she says. “I thought God made us

all and he gave us a profession when we came in here. I never thought I’d do anything else.”

There’s been a lot of acting in Armstrong’s 49 years. There’s also been a lot of “else”. Partly, that’s because

Australia is a small pond roiling with frustrated fish. Being mother to three sons – Sam, 18, and 12-year-old

twins Callum and Jai – has slowed things down at times, too. It’s also because Armstrong didn’t seize all her

opportunities when she worked in the US in the 1980s. For much of that time, she was part of the Actors’

Gang, a politicised theatre group led by Tim Robbins, who was also her boyfriend. “She is a really good

actress,” says Robbins from his office in New York. “She’s also a little bit mad. That’s a good combination.”

I meet Kerry Armstrong at her place, a comfortable back-road spread in Melbourne’s eastern hills. The

bungalow is calm and bright and homely. Her twins’ clothes are in neat piles on the floor, ready for a family

camping trip that begins the next day. The boys’ artwork dots the walls, along with the occasional movie

poster “starring Kerry Armstrong” and the requisite photos of the children, bowl-haired, when they were

small. There’s a positive-thinking homily tacked up in the toilet. A recipe book sits open on the kitchen

benchtop that Armstrong proudly tells me she tiled herself. “I like doing stuff. I jemmied up bricks, too,” she

says, gesturing to the laundry. Outside, her two dogs gallop back and forth on the lawn, chasing distant

planes. The twins (“my little guys”) are fishing on Port Phillip Bay. “They were on the internet yesterday

looking up how to trick snapper,” she says. “They always come back with fish.” There’s no man about the

house; Armstrong is single again, although she co-parents her three boys with their fathers.

Armstrong is dynamic and solicitous. She mixes lime cordial, offers to bake scones, pours potent homemade

wine (from the vines in her garden) and, later, presents plunger coffee with a choice of cheery mugs. While

the kettle boils, she goes to the bathroom, then bounds back, face split with a smile: “Did I have that parsley

skirt.

In conversation, she loops from winning to wary, scatty to serious, careful to reckless. She bungs on accents

and ploughs through anecdotes. She talks about buttonholing Al Pacino backstage at a New York theatre, she

reprises her precocious cowgirl creation, Hazeldene Yes-please, and she relives her first theatrical epiphany

as the 11-year-old narrator of The Little Prince.

At one point, she leaps into song and dance on the lawn. There’s joy and fun in all of it but she also reveals a

weary fear that she’ll be misinterpreted. “I’m desperate to find a clump of people who get me,” she says. “I

feel absolutely and utterly un-got.”

She seems prey to contradictory conversational impulses. On the one hand, she wants to put a lid on whatever

controversy might come from her words. She thinks hard. She takes long pauses, her silence like a transfixing

flame, letting the ice in her glass crackle to water. Then she looks at the ceiling and asks, “Care Bear, how do

I do this?” She waits for a reply as Paul Simon plays softly on a tucked-away stereo and, outside, the crows

out-gun the magpies for a spell.

And then Armstrong lets it rip, rolling through sentences as if her brakes are shot, crashing through any

suggestion that she might censor herself. So she tells me she’s been caught skinny-dipping in her pool (“I had

to hide behind a bush”). She says McDonald’s has a better work ethic than Australia’s budget film industry

(“They’re doing more to stop fast food than we are to stop fast tele−vision”). She laughingly suggests she’d

make a great slave (“I like doing things for people. If they fed me and I had a little cottage …”).

Some of the things she says are downright daffy (“Sometimes I’m working on things that look like a maze

and I’ve realised I’m probably better working on things that look like an ocean or a giant field”) but she’s so

sincere that I find myself nodding and thinking, “Yeah, an ocean, a field, exactly.” In this interview and in

telephone conversations over the next few weeks, it feels to me that Armstrong would love to trust the world

as she did when she was a teenager and it beckoned wide, wild and free.

Back then, everyone saw promise. Julia Blake, who plays Armstrong’s mother in the new ABC1 series Bed of

Roses, first worked with her in 1972 on a Henry James production for the ABC. Armstrong was 14. “She

arrived in her school uniform, the most beautiful girl,” says Blake. “She was enchanting, exuberant,

luminous. She had an innocence and a terrific appetite for life, and she worked hard, too.”

Armstrong’s high school drama teacher, Roma Hart, says she stood out straight away among the girls and

boys of St Leonard’s College, in Brighton. “When you teach drama you have one or two who have that extra

spark of talent. It’s a feeling they give you. If they’re going to cry they really imagine they’re crying. Kerry

always had that. She would throw herself wholeheartedly into everything.”

Hart recalls a class in which she asked the students to act as babies. “Suddenly, she wasn’t Kerry. She was

this little child, crawling up the podium. She gooed and gaaed and had the class in fits.”

Kerry had been performing since she was little, at first for her parents and two siblings at their home in

middle-class beachside Beaumaris. Her father, Norm Armstrong, was an avid Al Jolson and Frank Sinatra

fan, inspiring Kerry and her older sister, Kim, to stage regular Sunday night concerts with hairbrush

microphones. “Kim and Kerry used to sing and harmonise really beautifully,” says her mother, Bev. “It was

obvious that Kerry had something special. She’d light up the room.” Norm’s work as a conversion engineer

for gas companies moving from coal to natural gas took the family to Barcelona for two years when Kerry

was 11. As well as a school production of The Little Prince, Armstrong and her sister participated in mock

Eurovision contests in their apartment block. “My sister was Australia and I was Spain,” she says. “It was

good fun – joyous and free. And Spain would always win.”

Back in Melbourne, Armstrong sneaked off to sing Second Hand Rose at a general cattle call for theatrical

production company J. C. Williamson. “You had to be over 21 and I was only 15, so I lied about my age and

pretended I was a secretary,” she says. British comedian Sid James happened to be watching and offered

Armstrong a role in The Mating Season, a play that was to tour Australia.

Her parents forbade it. “We were happy to take her to acting classes but we weren’t thinking about a career,”

says Bev Armstrong. “But she was pretty distraught. She threatened to run away, she was really tragic about

it.” It was only after a quiet word from Bev’s mother – “Let her go, she was destined to act” – that Bev and

Norm relented.

Chaperoned by James’s wife, Armstrong travelled for nine months. She continued her studies by correspondence, then returned to year 11. “We thought, ‘She’s back at school, she’ll settle down,'” says Bev. Then, in 1977, Armstrong went off again with Doctor in Love, starring British comics Robin Nedwell and Geoffrey Davies. “We were worried about letting her go,” says Bev. “She was a stunning-looking young

woman by then. But she was also very sensible. We were very proud of her.”

Her parents weren’t so happy about her short stint as a scantily clad weather girl on Channel Nine, while still at school. “That’s something we try to forget,” says Bev. “We all regret that she did that.” Julia Blake remembers flicking on the television and seeing Armstrong with her pointer. “Terry!” she cried to her husband. “That’s the schoolgirl! What on earth is she doing the weather for? Why isn’t she acting?”

Armstrong was wondering the same thing. After she finished school, she did the TV rounds, with roles on Prisoner (framed country girl), Skyways (saucy country girl) and The Sullivans (cheap, broken-hearted suburban girl). The corollary was being slapped on the cover of TV Week wearing footy shorts and the like. “I don’t know what I was doing,” she says. “I wondered why the hell I wasn’t Katharine Hepburn, doing movies. Why wasn’t I with the Royal Shakespeare Company? I just wondered when the god of acting was going to get me out of this and I was going to start my life.”

Then, with veteran actor Bud Tingwell advising her to go overseas, Armstrong went to New York in 1981. There she studied with acting teacher Uta Hagen, whose alumni include Whoopi Goldberg and Jack Lemmon. Severe and exacting, Hagen asked her students to strive to be authentic, in the moment, and to conceal any thespian flourishes from the audience. Armstrong loved the serious attention to craft. She supported herself for a while by working as maitre d’ at iconic Central Park restaurant Tavern on the Green but soon picked up acting work, including a guest spot on Murder She Wrote, which entailed a move to Los Angeles. “There was a lot of talk about Hollywood,” says Armstrong, without much enthusiasm. She met Tim Robbins at a casting session. “She had a certain revulsion for LA,” says Robbins. “We help people with that problem in the Actors’ Gang.” Kerry Armstrong pitched in alongside Robbins, John Cusack and her regular understudy Helen Hunt.

“The Actors’ Gang allowed Kerry the opportunity to be an actress, to do work that challenged her, in the midst of Los Angeles,” says Robbins. “It’s a little oasis in a very superficial town.” One show, Violence, tackled issues such as suicidal Iowan farmers, hostages in Lebanon, the space program, abortion and microchipping. Halfway through, Armstrong would sing a ditty in whiteface to cut through the gloom. Gang members wrote shows collaboratively and pooled the earnings from their commercial work. Robbins did Moonlighting, Armstrong played Elena, Duchess of Branagh on Dynasty.

The door to A-list Hollywood was open but Armstrong couldn’t quite make herself walk through it. The lack of a green card was an issue, until she married US resident Alexander Bernstein, son of Leonard. “Alexander was my friend,” she says. “We didn’t consummate it.”

Sometimes, confidence was the culprit, as when she froze during a seal-the-deal reading for Fatal Attraction. Other times, she just said no. In 1986, she was offered an ongoing role on the star-making variety show Saturday Night Live and a three-picture deal with Universal Studios. “But it clashed with me doing Measure for Measure with the Arena Stage in Washington. Isabel is the largest female role in Shakespeare. My manager said, ‘I’m just going to mention it’s a three-picture deal, 15 grand a week, they’re going to make you a huge star. It’s a no-brainer.'”

Armstrong did the play. In 1987 she acted in Tom Stoppard’s Dalliance at the Long Wharf Theatre in New York. Later that year she came home. Why? “When people started to clamour around me and tell me their plans, tell me I was going to be a big star, I’d go walkabout, go surfing, disappear a bit. I like being in the group. I love an ensemble. I liked coming second.”

What kind of career might she have had if she had stayed in the US? Robbins gets grumpy when I ask him to speculate. “I hate that kind of stuff,” he says. “The town of Los Angeles is littered with actresses that could’ve, could’ve, could’ve. I don’t buy it. No one should live their life that way. I hope she doesn’t have any regrets.”

But Bev Armstrong, for one, thinks her daughter’s career would have flourished if she’d stayed in America. “She was homesick. My mother had died. She decided to come home and she didn’t go back,” she says. “It’s a pity she didn’t stay that bit longer. She was finally getting recognition as a serious actor.”

Bev also tells how the family fell about in agony when Helen Hunt won an Academy Award in 1998. “Helen used to say, ‘Oh God, I wish I could act like Kerry.’ We thought that could have been Kerry. I think we all have regrets.”

Armstrong felt honoured and cherished in the US. She doesn’t always feel the same way in Australia. “There are times I want to walk out of this country and go overseas,” she says. “When I go to England, there’s a wonderful sense of freedom of speech, you don’t get misinterpreted. In America I found so many like-minded people who were all working. We don’t look after our artists here, so we have lots of unhappy ones.”

She has acted in quality Australian theatre, television and films since 1987, most notably Lantana and SeaChange, both of which earned her AFI awards in 2001. But the quality projects have been interspersed with pay-cheque pragmatism: tax-dodge movies, some crappy TV, a pasta advertisement and Dancing with the Stars.

“The day they asked me was the day I got the school fees for Sam. It fitted in extraordinarily well,” she says of the latter. In 2003, she wrote The Circles, a self-help book that explains Armstrong’s theory of placing people she knows in one of seven concentric circles, depending on how close or influential she wants them to be.

“I spent much of my life being interpreted by people in ways I found baffling,” she says. “I wrote it so I could be free.” Right now, she’s midway through another of her periodic giving-up-acting crises. She reckons she might become a counsellor to help “young women who have the world at their feet”, and has enrolled in a counselling course by correspondence.

Part of what she wants to be free from is the view that she’s hot totty. She’s frustrated that her appearance has been a focus throughout her career. “People tell me that my skin looks good. People are actually looking at the sausage skin, for f…’s sake. I mean honestly, really, when are we going to get bored with it?” She despairs that, even now as she approaches 50, people are bringing her strapless dresses to try on for the Logies. “It doesn’t matter what I do, I don’t get fat,” she laments. “I’d love to be a blowfish but it seems that in Australia,

it’s once a salmon, always a salmon.”

Armstrong has recently broken up from her fifth serious relationship. What is it about her and men? “I think sometimes I’ve been happy with people who were either unhappy themselves or we couldn’t find happiness together and it probably wasn’t my job to make them happy. I think what’s interesting is when you’ve got a job that you love and you’ve got family that you love, that’s pretty lucky, so I probably need to choose people who love life, who want to be right where they are. I’m kind of usually pretty happy where I am.” Well, that clears that up.

She’s in awe of her parents, who recently celebrated 50 years of marriage. “They called each other ‘my best friend and lover’ and they did a bit of a dance. She had her bridal veil on. Wow. My mother is a great example of a girl who knew what she wanted and then decided how to make it work. I have no idea how to do that. Not yet, anyway.”

She does know that she wants to make the world better. Tim Robbins was impressed by her instinctual response when they saw a man stabbed in downtown Los Angeles. “She got out of the car and dealt with him, talked to him in Spanish, kept him alive until the ambulance got there,” he says. “That’s the kind of person she is. Most people would just drive by and go ‘ew’. ”

In 2003, Armstrong led a protest against the Iraq War because “my little guys were frightened”. Since 1999, she’s been a key contributor to Big hART – a socially conscious theatre organisation run by playwright Scott Rankin – donating her time to work on projects with street kids, rural youth at risk, domestic violence victims, elderly people in public housing and fragile single mothers. “She has a deep sense of right and wrong,” says Rankin. “She’s the opposite of egotistic and myopic. If she comes to a Big Hart project she comes to disappear herself and serve the project. She brings her gift alongside people.” Rankin rates her acting ability highly. “Kerry has an inspirational shaman-like ability to conjure something that’s not actually there,” he says.

Darren Ashton directed Armstrong in the 2007 dance mockumentary Razzle Dazzle. “She always searches for the truth,” he says. “It’s all about being in the moment. She doesn’t do what the script says, she does what the scene requires. That’s what makes her a great actress.”

That’s also why she has a reputation for being difficult to work with. “Nobody fights and works as hard on a role as Kerry does,” says Ashton. “She’s very vocal. You’ll have discussions, she’ll try something, we’ll talk about it for another half an hour, you’ll get a call from her at night. It’s unrelenting. You have to be up for it, because at the end of it is a great performance. A director who doesn’t think Kerry Armstrong is a genius really needs to look at the way they work.”

Ray Lawrence directed Armstrong in Lantana and would love to work with her again, even though he finds her baffling. “I don’t always understand what she’s saying,” he says. “I remember she was trying to explain something about her character to [Lantana co-star] Anthony LaPaglia and me. After five minutes we still didn’t understand, so we told her to just do it.

“She works on a special level, it defies description, but she doesn’t let you down. A lot of the time she has things in her head that are abstract, like music, you have major and minor and everything in between. She’s a bit like a musical instrument. Sometimes it’s better to sit back and listen.”

Rankin thinks Armstrong will thrive as the prison of beauty crumbles. “She was scarred by being so

physically beautiful. Now, as that’s not the preoccupation, she’s not a goddess, there’s more room for her to be

more complex, take more interesting roles.”

He reckons the camera will love her even more. “If you look at her in the lens, at the scale of her face, the way her cheekbones and mouth work, it’s like she’s more than 3D. That’s why the camera eats her up.” Bring it on, says Armstrong. “I don’t have a feeling of having a use-by date. Acting has never been about a time line, it’s been about storytelling.”

She’s looking forward to seeing where the Kerry Armstrong story takes her. “When I was little, stories were so exhilarating, it was such a good world,” she says. She’s happiest when she’s in the moment, whether that’s submerged in a role, patching up a 12-year-old knee, or seeing people “who are in absolute awe of what’s going on, really present, affected and moved by something”.

Armstrong surfs with her own boys now, though at a respectful distance. “How embarrassing would it be to have your mum dropping in on you?” She wears contact lenses in the water because, these days, whatever it is, whenever the moment, wherever the wave, Kerry Armstrong wants to see it coming.

kerry armstrony kerri ann kennedy

Hi Vanessa, Hope you enjoyed the piece!

Hi Dani

What an enjoyable read. I once saw Kerry in a chemist in Balnarring on the Mornington Peninsula where l live. I was elated as l have always loved Kerry and knew she was a true talent. I was 90% sure it was her, however the 10% unsure that l was made me ask her “are you Kerry Armstrong”. With a beautiful big smile that she portrays she answered “yes l am”.

I went on to tell her that my daughter who was with me did not believe me when l said it was you. She was so warm and said “your daughter should listen to her Mum”. She winked and smiled again before leaving the chemist. I felt very privileged to have crossed paths with such a special soul!!

Hi Margy,

Wow, what a great story! Thank you for sharing. Kerry is a very special person.